The Bahamas (Northern Region)

Turks and Caicos

Amsterdam

Cyprus

Cayman Islands

Jamaica

Barbados

British Virgin Islands

March 06 2025

What happens if a client or supplier doesn’t hold up their end of the deal?

You know it well: It could leave you exposed to financial losses, delays, or worse.

That is unless you hire a commercial contracts lawyer upfront to help you nail down the right remedies for breach of contract during your contract negotiations.

This article is your go-to guide for understanding what remedies you can negotiate in your contracts, and why you need them. From securing damages and enforcing performance to preventing future breaches, we’re digging deep into each of them to make sure you’re covered in case things go wrong.

Let’s get started.

A breach of contract happens when one party doesn’t hold up their end of the deal. In the context of buying and selling goods, it can look like:

The Sale of Goods Act separates breaches of contract into two categories: conditions and warranties.

Regarding conditions, if the seller fails to meet one (like delivering the right product), the buyer can cancel the contract and demand a refund.

As for warranties, these are smaller issues that don’t ruin the whole deal but still warrant compensation.

When a contract gets broken, your business isn’t just left to deal with the mess—it has legal options.

The right remedy depends on what went wrong and how you want to fix it.

Do you want compensation for your losses? Do you need the contract to be enforced as originally agreed? Or do you just want to walk away and cut your losses?

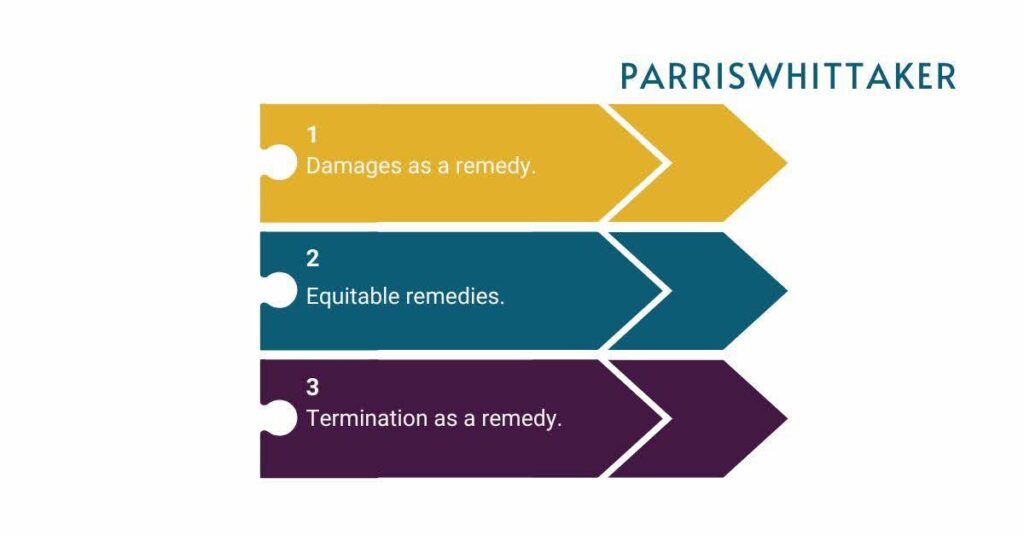

Legal remedies for breach of contract fall into these 3 main categories:

When a contract is breached, money is often the first thing on the table. And for good reason—damages are the most common remedy, designed to put the injured party in the position they should have been in if the contract had been honored.

But not all damages are created equal. That’s why damages are split into two main types:

Take the UK case of Hadley v. Baxendale (1854), a textbook example of how courts decide damages. Hadley, a mill owner, sued after a delayed crankshaft delivery shut down his business. The court ruled that only foreseeable losses could be recovered—meaning if Baxendale didn’t know the delay would cause major financial harm, he couldn’t be held responsible for lost profits.

Translation: If damages aren’t predictable, they may not be recoverable.

But sometimes, the harm caused by a breach isn’t about money. For instance, in Ruxley Electronics v. Forsyth (1996), Forsyth hired Ruxley to build a deep swimming pool, but they built it too shallow. It still worked, but it wasn’t what he paid for. The court ruled that since fixing it would cost way more than the actual loss in value, Forsyth was entitled to “loss of enjoyment” damages instead.

If you’ve heard of both, here’s a clarification of what each means:

While damages aim to compensate, restitution aims to prevent unjust enrichment. It forces the breaching party to return any benefits they unfairly gained from the contract.

Say you hired a caterer for a corporate event and paid in full upfront. But on the day of the event, they only delivered half the food and left. You could claim damages for the cost of scrambling to find last-minute replacements. But you could also demand restitution—forcing the caterer to return the money they took for services they never fully provided.

Courts use restitution when damages alone don’t feel like justice.

To sum it up: If you lost money because of the breach, go for damages. If the other party gained something unfairly at your expense, go for restitution.

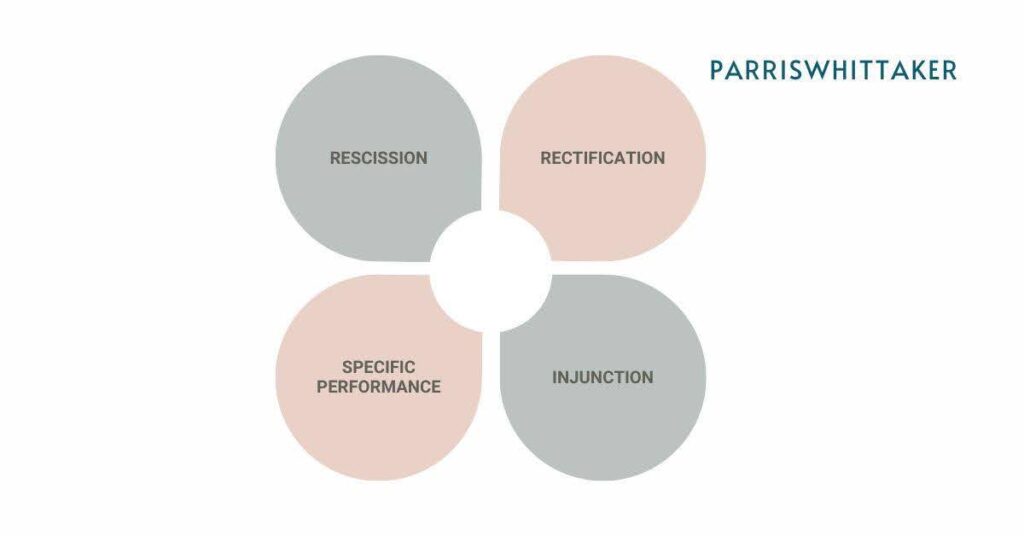

Instead of just compensating losses, equitable remedies focus on fairness—undoing the breach, correcting mistakes, or even forcing a party to follow through on their obligations.

Depending on the situation, courts can:

Let’s break these down and see when each one applies:

Rescission is the legal equivalent of hitting undo on a bad contract. If you were misled, pressured, or dealing with a major breach, it’s one of the strongest remedies at your disposal.

But it’s not a free-for-all—you need a solid legal reason to make the contract vanish.

Typically, courts only allow rescission when:

Take the UK case of Derry v Peek (1889) as an example. A company lied about having a government license to run steam-powered trams. Investors bought shares based on this false claim, only to find out the license never existed. The investors sought rescission, arguing they were misled.

While this case set a high bar for proving fraudulent misrepresentation, it also showed how deceit can make a contract disappear.

Still, you should know that rescission isn’t always an option. In fact, courts might refuse it if too much time has passed, you knew about the breach but continued with the agreement anyway, or if rescinding the contract would unfairly impact someone else (like a buyer down the chain).

Unlike the prior remedy, where the court scraps the contract, rectification is aimed at fixing the mistake to what was actually intended (e.g., maybe a typo changed the meaning of an important term).

To use rectification as a remedy, you need to prove that either both parties made the same mistake or one party made a mistake, and the other party knew but stayed quiet to gain an unfair advantage. (Fun fact: The latter is called “unilateral mistake with sharp practice.”)

Here’s an example:

In Joscelyne v Nissen (1970), a father transferred his taxi business to his daughter in exchange for her paying his expenses. But the written contract forgot to mention that she had agreed to cover his gas and electricity bills. When she refused to pay, he sued. The court granted rectification—because both had genuinely agreed to this, even if it didn’t make it onto paper.

To put it in business terms: You sign a contract to sell your business for £500,000, but the final document mistakenly says £50,000. If both parties meant £500,000, rectification ensures the contract reflects that.

Fair?

If all you really want is for the other party to do what they promised, specific performance is your go-to breach of contract remedy.

You should know that this remedy is extremely rare, though, and for a good reason—courts don’t like forcing people into deals unless it’s absolutely necessary.

Specific performance makes sense when:

A classic example?

Imagine you’re a tech startup, and you signed a contract for custom-built software to be developed just for your company. The developer suddenly decides not to deliver. Damages might not help, because no off-the-shelf product can replace what you were promised. In this case, you could ask the court to enforce specific performance.

Also, keep in mind that the court won’t grant specific performance when it requires constant supervision or causes extreme financial difficulty to the other party—or to force someone to work against their will (though they might issue an injunction to stop them from working elsewhere!).

Instead of awarding damages or forcing a party to follow through with their contractual obligations (specific performance), courts can also order someone to stop doing something—or, in some cases, to do something specific.

In relation to that, there are two main types of injunctions as remedies for breach of contract:

Courts grant injunctions when the breach would cause serious harm, there’s a clear contractual obligation, and if damages aren’t enough on their own.

A classic case of where an injunction might be ordered is to stop an ex-employee from leaking confidential information—like if a high-level executive jumps ship to a competitor and starts sharing trade secrets.

Also, if a former partner launches a rival business in breach of a contract, an injunction can prevent them from operating in the same market.

Quite a remedy, isn’t it?

When a breach of contract happens, sometimes the only solution is to walk away.

Termination, the legal process of ending the contract because one party has failed to perform their obligations, serves that purpose specifically.

The moment termination happens, any further obligations under the contract are wiped out, and both parties are free from any promises or duties that were supposed to be carried out.

But how do you actually terminate a contract?

The most important thing for you to know is that to terminate a contract, you typically need to give the other party a notice of breach and a deadline to make things right, if applicable.

Keep in mind, though, that if the termination is unjust, it could expose you to damages – so make sure you contact ParrisWhittaker commercial contracts attorneys prior to making any serious legal moves.

What are the time limits for seeking remedies for breach of contract?

Timing is, indeed, important when it comes to breach of contract claims – and you can find all about it in The Limitation Act 1980.

In most cases (we’re talking standard contracts), you’ve got six years from the date of the breach to bring a claim. By “the date of the breach,” we’re talking about the moment the breach actually happens—not when the damage occurs, when you notice the issue, or when you eventually suffer loss.

If you don’t act within this period, you could be barred from bringing a claim.

Now, if your contract was executed as a deed (meaning it was formal and signed in a special way), you get twelve years instead of just six.

Why the difference?

Because deeds are seen as more serious, so the law gives you a little extra breathing room.

However, life isn’t always black and white, and the Limitation Act allows for some exceptions.

For instance, fraud or the concealment of facts can pause the time limit until the truth comes out.

Additionally, contractual clauses can play a role here. Parties can agree to shorter or longer limitation periods, but these have to meet legal requirements. You can’t just decide to make it shorter than six years without consequences.

Timing is everything when it comes to claiming remedies for a breach of contract. The clock starts ticking from the moment the breach happens, so mark your calendar from that day.

And don’t go it alone. Contact ParrisWhittaker commercial contracts attorneys today to help you determine the best course of action, make sure you’re within the legal timeframe, and clarify if any exceptions or special circumstances might apply to your case.

CLOSE X