The Bahamas (Northern Region)

Turks and Caicos

Amsterdam

Cyprus

Cayman Islands

Jamaica

Barbados

British Virgin Islands

February 25 2025

Seaworthiness of the vessel is the backbone of all shipping contracts—and, if you’re a shipowner or carrier, understanding what it means legally can make or break your business.

Here’s why you should care:

Now, you might think you’ve got everything under control, but this topic is trickier than it seems.

So, stick around to find out how seaworthiness could change your approach to contracts and keep you safe from unexpected costs. Trust us, it’s worth it.

If we were to define the seaworthiness of the vessel outside of the legal context, it’d sound really simple: A ship that can sail without sinking.

But legally? It’s a whole other story.

Different laws define it in different ways, and those definitions can decide who bears the costs when things go wrong.

For starters, you should know that it’s the Hague Rules & Hague-Visby Rules that govern most international shipping contracts. They say a ship must be seaworthy “before and at the beginning of the voyage.”

However, the carrier (shipowner) doesn’t have to guarantee seaworthiness. They just have to exercise due diligence to make sure the ship is fit (we’ll talk more about this later).

English law takes a stricter approach, especially its case law. For instance, in McFadden v. Blue Star Lin (1905), the court took a stance that seaworthiness means the ship must be:

Meaning: If the ship isn’t seaworthy when it leaves port and throughout the journey, the owner is in trouble, whether they knew about the ship having a defect or not.

Then, there’s also SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea), which doesn’t explicitly define seaworthiness but makes rules that contribute to it.

For example, a ship must have proper fire safety and lifeboats, a good passage plan, and equipment that meets international safety standards.

If a ship fails to meet these standards, it’s not seaworthy by default—even if Hague-Visby or English law says otherwise.

Lastly, the Bahamas legislation follows English law principles but also aligns with Hague-Visby, meaning that shipowners must exercise due diligence, but if the ship is found unseaworthy at the start of the voyage, they’re liable no matter what.

You may not have known this, but a vessel can be physically seaworthy but still legally unseaworthy if it doesn’t meet regulations.

For example, a yacht with a strong hull and working engine may be physically seaworthy, but if it’s missing life jackets or has an untrained captain, it could be legally unseaworthy.

Similarly, a cargo ship with a mechanical defect that could’ve been fixed is both physically and legally unseaworthy.

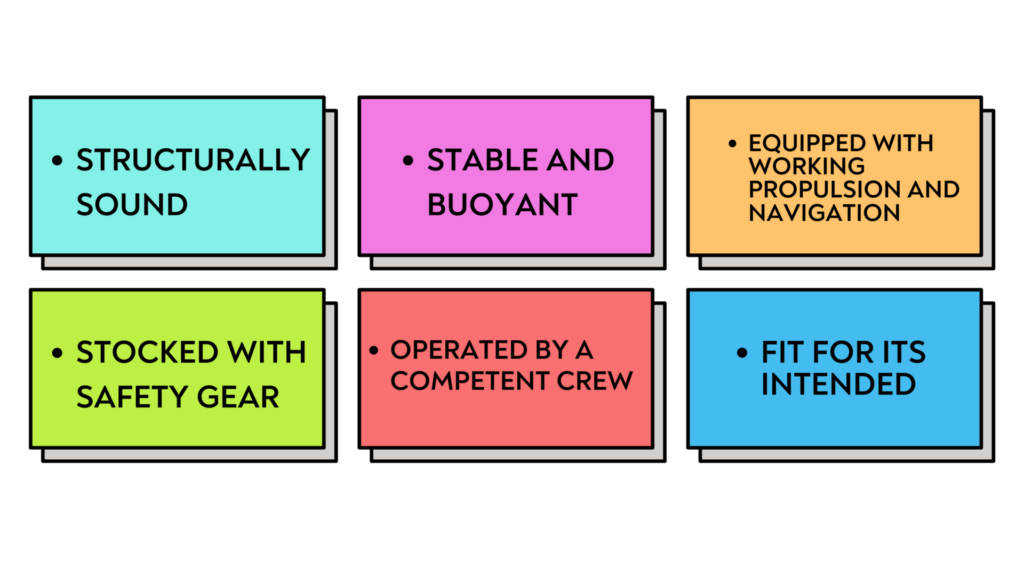

So, what makes a boat seaworthy on both of these fronts? The final answer is that a boat is seaworthy when it is:

If any of these are missing? The boat isn’t seaworthy—legally or practically.

Remember how we mentioned that shipowners don’t have to guarantee seaworthiness, just show they exercised due diligence to ensure the ship was fit for the journey? Here’s what that actually means:

Due diligence means proving the shipowner took all reasonable steps to ensure the ship’s seaworthiness. The tricky part is that the court set a high bar for what counts as “reasonable steps.”

For instance, if an issue could have been detected through proper maintenance or inspections, and damage occurs to the cargo, the shipowner can’t claim they exercised due diligence. In that case, the shipowner will be held liable.

For instance, in the CMA CGM Libra Case (UK Supreme Court, 2021), the ship ran aground due to an inaccurate passage plan—something that should have been fixed before departure. The court ruled that this inadequate passage plan made the ship unseaworthy, even though the vessel itself had no mechanical defects.

The key takeaway? Due diligence isn’t just about the physical condition of the ship—it also extends to operational preparedness.

On the other hand, in The Eurasian Dream (English Court of Appeal, 2002), a defect in the engine cooling system caused damage to cargo. The shipowner argued they had performed routine inspections and the defect wasn’t detectable.

In that case, the outcome was wildly different, and the court ruled in favor of the shipowner, saying they had exercised due diligence because the issue was a latent defect that couldn’t have been found with reasonable inspections.

Moral of the story? Ignorance isn’t a defense—if a defect could have been found, shipowners are responsible.

Now that we’ve established that a shipowner can avoid liability for cargo damage caused by unseaworthiness by proving they took all reasonable steps to maintain the vessel, let’s explore how this is done.

Namely, this is done through:

If a shipowner can’t prove seaworthiness in any of these ways, they’re on the hook for damages. Even worse, insurance providers may argue that if the vessel was unseaworthy at the commencement of the voyage, the risk was fundamentally increased, leading to an exclusion of coverage.

Shipowners can sometimes avoid liability if the damage was caused by something out of their control—think acts of God or inherent defects in the cargo itself. But that’s a tough argument to win without an expert maritime law attorney.

One bad decision can cost you big. Don’t let one mistake jeopardize your business—Contact ParrisWhittaker maritime law attorney today and make sure you’re on solid ground.

CLOSE X